Approaching the Market

| Site: | Saylor Academy |

| Course: | BUS203: Principles of Marketing |

| Book: | Approaching the Market |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Sunday, 18 May 2025, 3:05 PM |

Description

Read these sections.

Approaching the Market

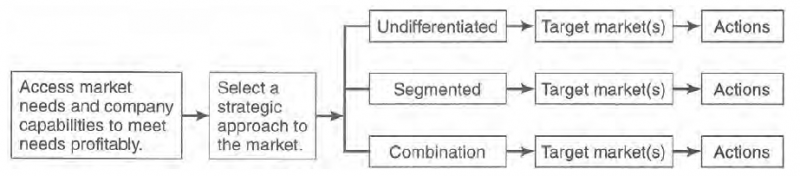

All the parties in an exchange usually have the ability to select their exchange partner(s). For the customer, whether consumer, industrial buyer, institution, or reseller, product choices are made daily. For a product provider, the person(s) or organization(s) selected as potential customers are referred to as the target market. A product provider might ask: given that my product will not be needed and/or wanted by all people in the market, and given that my organization has certain strengths and weaknesses, which target group within the market should I select? The process is depicted in Figure 2.1.

This text was adapted by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work's original creator or licensor.

This text was adapted by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work's original creator or licensor.

The Undifferentiated Market (Market Aggregation)

The undifferentiated approach occurs when the marketer ignores the apparent differences that exist within the market and uses a marketing strategy that is intended to appeal to as many people as possible. In essence, the market is viewed as a homogeneous aggregate. Admittedly, this assumption is risky, and there is always the chance that it will appeal to no one, or that the amount of waste in resources will be greater than the total gain in sales.

FIGURE 2.1 Approaches to the market

For certain types of widely consumed items (e.g. gasoline, soft drinks, white bread), the undifferentiated market approach makes the most sense. One example was the campaign in which Dr. Pepper employed a catchy general-appeal slogan, "Be A PEPPER!", that really said nothing specific about the product, yet spoke to a wide range of consumers. Often, this type of general appeal is supported by positive, emotional settings, and a great many reinforcers at the point-of-purchase. Walk through any supermarket and you will observe hundreds of food products that are perceived as nearly identical by the consumer and are treated as such by the producer - especially generic items.

Identifying products that have a universal appeal is only one of many criteria to be met if an undifferentiated approach is to work. The number of consumers exhibiting a need for the identified product must be large enough to generate satisfactory profits. A product such as milk would probably have universal appeal and a large market; something like a set of dentures might not. However, adequate market size is not an absolute amount and must be evaluated for each product.

Two other considerations are important: the per unit profit margin and the amount of competition. Bread has a very low profit margin and many competitors, thus requiring a very large customer base. A product such as men's jockey shorts delivers a high profit but has few competitors.

Success with an undifferentiated market approach is also contingent on the abilities of the marketer to correctly identify potential customers and design an effective and competitive strategy. Since the values, attitudes, and behaviors of people are constantly changing, it is crucial to monitor these changes. Introduce numerous cultural differences, and an extremely complex situation emerges. There is also the possibility that an appeal that is pleasing to a great diversity of people may not then be strong or clear enough to be truly effective with any of these people. Finally, the competitive situation might also promote an undifferentiated strategy. All would agree that Campbell's dominates the canned soup industry, and that there is little reason for them to engage in much differentiation. Clearly, for companies that have a very large share of the market undifferentiated IT market coverage makes sense. For a company with small market share, it might be disastrous.

Product Differentiation

Most undifferentiated markets contain a high level of competition. How does a company compete when all the product offerings are basically the same and many companies are in fierce competition? The answer is to engage in a strategy referred to as product differentiation. It is an attempt to tangibly or intangibly distinguish a product from that of all competitors in the eyes of customers. Examples of tangible differences might be product features, performance, endurance, location, or support services, to name but a few. Chrysler once differentiated their product by offering a 7-year/70,000-mile warranty on new models. Pepsi has convinced many consumers to try their product because they assert that it really does taste better than Coke. Offering products at a lower price or at several different prices can be an important distinguishing characteristic, as demonstrated by Timex watches.

Some products are in fact the same, and attempts to differentiate through tangible features would be either futile or easily copied. In such cases, an image of difference is created through intangible means that may have little to do with the product directly. Soft drink companies show you how much fun you can have by drinking their product. Beer companies suggest status, enjoyment, and masculinity. Snapple may not taste the best or have the fewest calories, but may have the funniest, most memorable commercials. There tends to be a heavy emphasis on the use of mass appeal means of promotion, such as advertising, when differentiated through intangibles. Note the long-term use of Bill Cosby by Jell-O to create an image of fun. Microsoft has successfully differentiated itself through an image of innovation and exceptional customer service.

There are certain risks in using product differentiation. First, a marketer who uses product differentiation must be careful not to eliminate mention of core appeals or features that the consumer expects from the product. For example, differentiating a brand of bread through its unique vitamin and mineral content is valid long as you retain the core freshness feature in your ad. Second, highlighting features that are too different from the norm may prove ineffective. Finally, a product may be differentiated on a basis that is unimportant to the customer or difficult to understand. The automobile industry has learned to avoid technical copy in ads since most consumers do not understand it or do not care.

However, there is a flip-side to product differentiation, an approach toward the market called market segmentation.